Emily Thomas:

The Meaning of Travel (2020)

Will Space Travel Show The Earth Is Insignificant?

I think the difference between everyday journeys and travel journeys lies in how much

When and where do people feel otherness? That depends on who we are. Human beings each possess a unique set of memories, desires, beliefs. Language, food, or architecture that is familiar to one person may not be familiar to another.(p.18)

Travelling can change the way we feel about our home places. Before voyaging abroad, you might believe your home town to be the most beautiful, most important place in the world. It is unlikely you will feel that way on your return. In this vein, Socrates once quelled a wealthy landowner by showing him that his ‘great' estate cannot be found on a world map. Grand Tour bear master Richard Lassels remarks that travelling takes noblemen down a few notches in their pride, for they see how small their lands and countries are. Novelist Gustave Flaubert agrees that travelling makes you modest: ‘You see what a tiny place you occupy in the world.' By showing how large the world is, travel reveals how small our home places are.

Of course, the

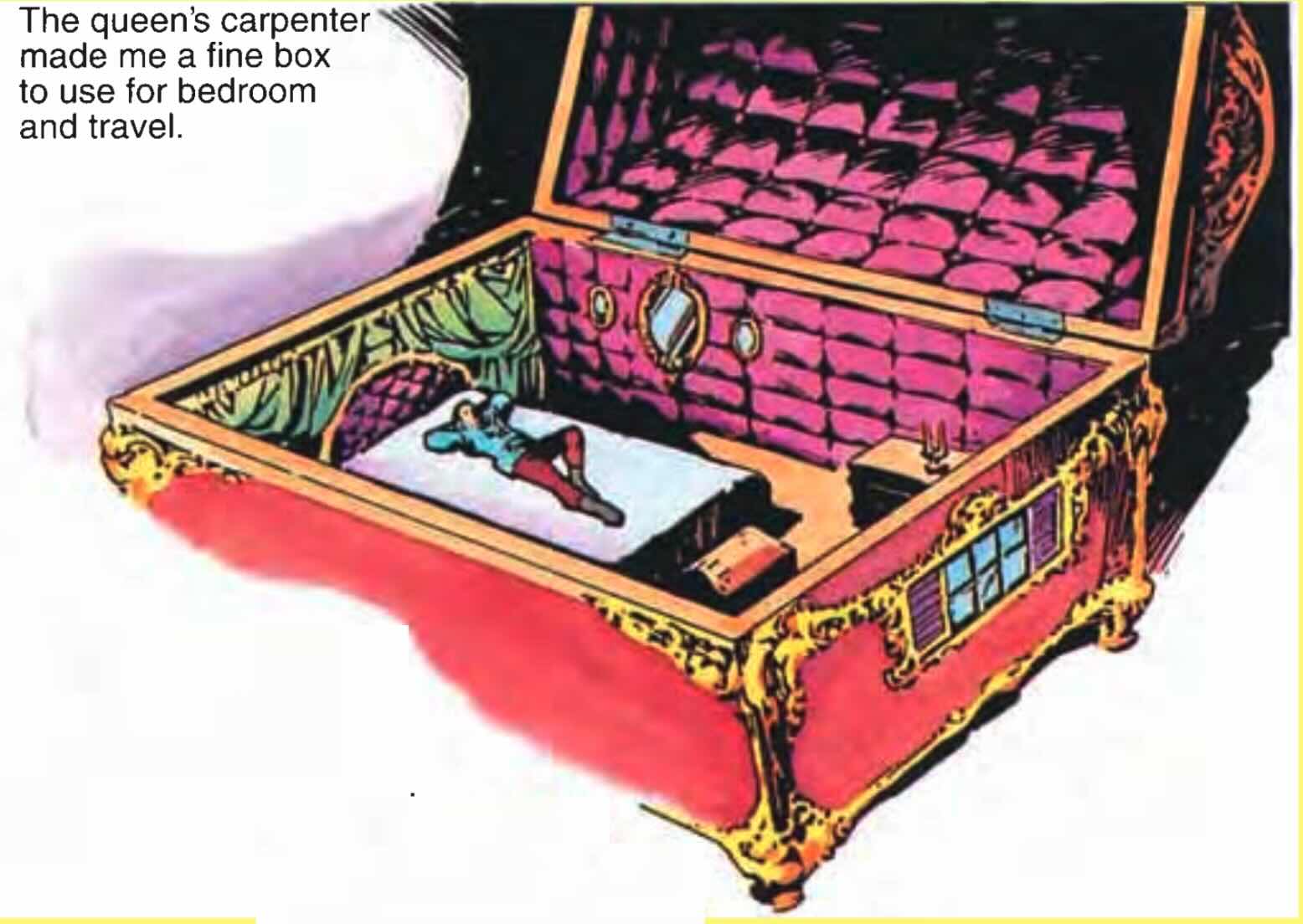

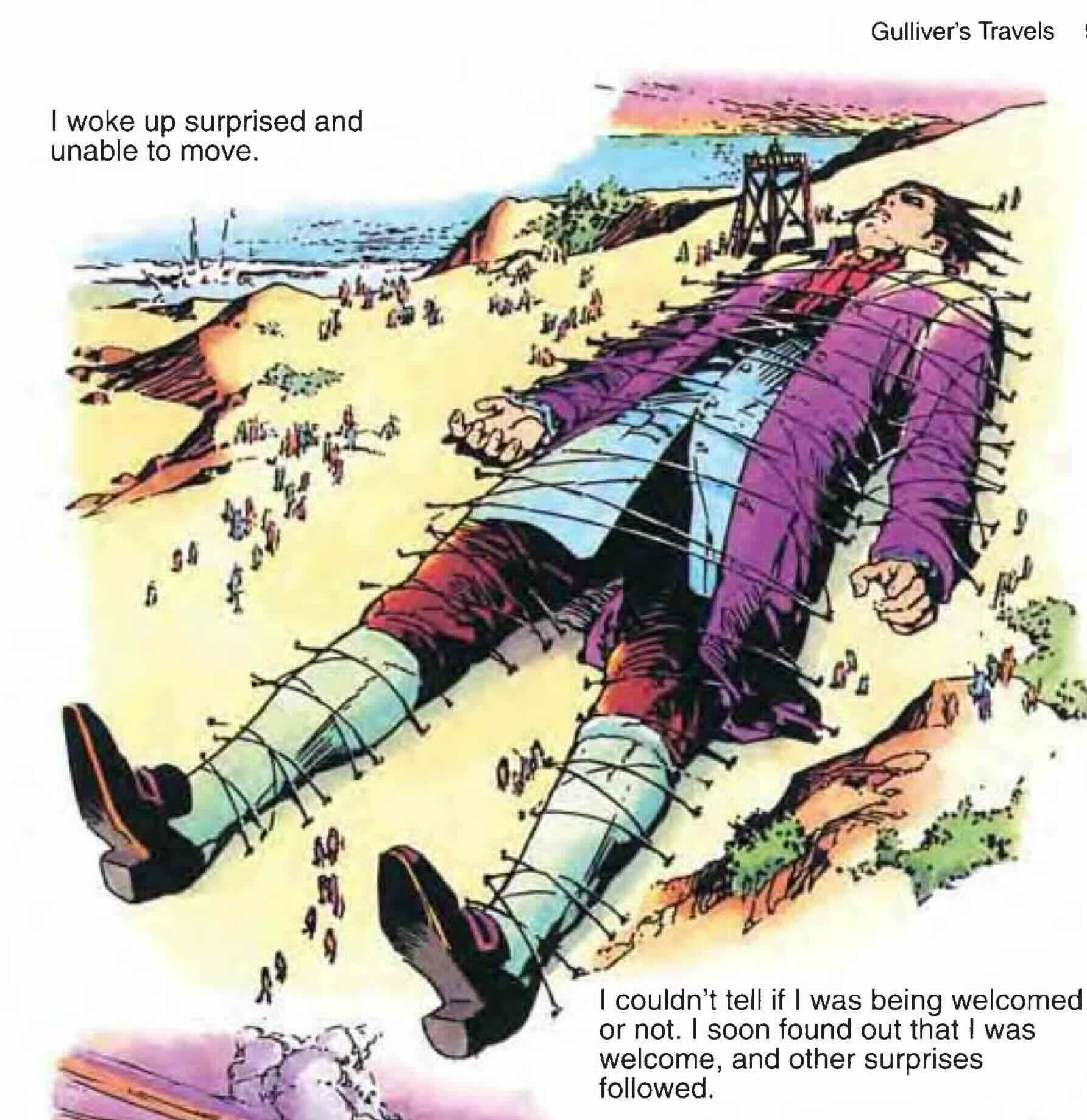

Similarly, take the Lilliputians described in Gulliver's Travels. Gulliver portrays these people as miniature humans, standing around six inches tall. The Lilliputians live in little houses, and work in little towns. Like us, each Lilliputian is a thinking, feeling being. If they really existed, I believe we would and should value their lives as highly as our own. We value children's lives as highly as adults' lives, the lives of slim or short people as much as those of plump or tall people. During an evacuation, nobody shouts, ‘Large people first!'.

So, the size of a thing need not affect its value. A painting can be beautiful regardless of its size, and a person's life is valuable whether they are a giant or a Lilliputian. In 1951, Bertrand Russell made precisely this point:

"There is no reason to worship mere size. We do not necessarily respect a fat man more than a thin man. Sir Isaac Newton was very much smaller than a hippopotamus, but we do not on that account value him less."

If there is no connection between size and value, the size of your home place should not devalue it. The problem is, when we come to realize how small our home places are, our attitudes towards them often change. What is going on? We can answer this question using Guy Kahane's distinction between

"Seen alongside the horrific (or the wonderful), many things become simply insignificant— worthy of no attention at all. If you witness a terrible tragedy, it would be inappropriate to obsess about a stain on your suit. After spending a week attending to soldiers injured and disfigured in the civil war, Whitman wrote to his mother that ‘…really nothing we call trouble seems worth talking about.'"

To give another example, consider Van Gogh's painting of a cherry blossom. This painting has intrinsic value as a beautiful artwork. Imagine you are looking at this painting in Amsterdam's Van Gogh Museum, alongside many of his other paintings. An art critic might say this particular painting is somewhat important, as a milestone in Van Gogh's artistic development. Now imagine that his other paintings were all destroyed. This blossom painting would become momentously important, as the last remaining example of Van Gogh's work.

The idea is that the intrinsic value of a thing is unchangeable, but its significance can change. The aesthetic value of a Van Gogh painting remains the same no matter what. Yet, if the painting became the last of its kind, its significance would increase.

One way the significance of a thing can change is by placing it in a

[這種意義的轉變,就是我們旅行時會意識到的事。]

If I stayed on my train all the way to its final destination, I would arrive at Leeuwarden. This is a miniature jewel of a city, flaunting a medieval centre looped by canals, crowned by a leaning bell tower. Within the northern Netherlands, Leeuwarden is extremely significant, a historic and graceful state capital. However, its significance pales the farther away you get. By European standards, Leeuwarden is relatively insignificant: it is one of a thousand medieval cities. This is why travel makes you modest. Although your home place retains its value no matter how far you travel, you become conscious of its insignificance.

If travelling from Fairbanks to Amsterdam can induce a feeling of insignificance, what might space travel do? As novelist Douglas Adams once wrote in his Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy, ‘Space is big, really really big…'.

I said above that the Earth lies 140 million miles from Mars. Our nearest stars, the Alpha Centauri system, are 4 light years away—that's around 25 trillion miles. Our galaxy, the Milky Way, contains anywhere from 100 to 400 billion stars. Scientists estimate that the observable universe is around 93 billion light years across. The whole universe is at least 250 times as large as the observable universe, and it may be infinite. Our brains weren't built to comprehend these numbers.

Philosophy and science fiction are littered with remarks connecting the size of the universe with human insignificance. As Adams puts it:

"Far out in the uncharted backwaters of the unfashionable end of the western spiral arm of the Galaxy lies a small unregarded yellow sun. Orbiting this at a distance of roughly ninety-two million miles is an utterly insignificant little blue-green planet."

Such sentiments go back a long time.

In antiquity, the philosopher Cicero authored a short story on this theme. The Dream of Scipio describes how a Roman general, Scipio Aemilanus, travels to a ‘place on high, full of stars, and bright and shining'. Whilst watching the Milky Way, ‘the surpassing whiteness of its glowing light', Scipio writes:

"And as I surveyed them from this point, all the other heavenly bodies appeared to be glorious and wonderful, — now the stars were such as we have never seen from this earth; and such was the magnitude of them all as we have never dreamed; and the least of them all was that planet, which farthest from the heavenly sphere and nearest to our earth, was shining with borrowed light, but the spheres of the stars easily surpassed the earth in magnitude — already the earth itself appeared to me so small, that it grieved me to think of our empire, with which we cover but a point, as it were, of its surface."

Scipio is seeing how small our planet is, and how the great Roman Empire is even smaller than this. Observing Scipio, his grandfather tells him:

"I see .... that you are even now regarding the abode and habitation of mankind. And if this appears to you as insignificant as it really is, you will always look up to these celestial things and you won't worry about those of men. For what renown among men, or what glory worth the seeking, can you acquire?"

This is a thought experiment. In asking us to imagine interstellar space travel, Cicero is asking us to reconsider the significance of our lives. In his Pensées (literally, Thoughts), the French philosopher Blaise Pascal writes:

"When I consider the short duration of my life, swallowed up in the eternity before and after, the little space which I fill, and can even see, engulfed in the infinite immensity of spaces of which I am ignorant, and which know me not, I am frightened."

The eternal silence of these infinite spaces frightens lots of us.

Many thinkers are awed by the littleness of humans and our planet. When we reflect on the immensity of the universe, should we conclude that humankind and Earth are insignificant? Russell considers this question. He writes that although we find the minute size of humankind in the astronomical abyss ‘bewildering and oppressive', our reaction is not rational. As he believes we

Kahane develops Russell's position into a larger argument. Kahane argues that although there is something embarrassingly megalomaniac in the desire for grand cosmic significance, this desire might be fulfilled. Kahane's reasoning runs as follows.

Suppose we are right to value life more highly, that plants and animals really do have a higher intrinsic value than non-living things. This would mean our planet is valuable and significant within the context of our solar system. The sun, the moon, Mars, and Jupiter are impressive. But they are merely clumps of rock and gas. We would be small, yet we would maintain our importance. And the significance of Earth may not stop there. Kahane argues if there is extraterrestrial life on other planets, the significance of Earth may decrease. In the same way that Groningen's significance decreases in the context of other European cities, our planet would be less important if it were merely one of many living planets. Yet, if our planet is the only living planet in the universe, it would be of gigantic cosmic significant. As Kahane writes:

"When we are impressed by our tiny size, by the vastness of the space that envelopes us, and conclude that we must be very unimportant, this may be because we forget to consider just how empty this immensity is. An observer might take a very long time to find us in this immensity, but besides us, he might find in it little or nothing to care about."

If we are alone in the universe, the importance of our little blue-green planet may outweigh its size. Our home planet might be tiny and the most significant thing in the entire universe. I don't know whether there is life on other planets. That's a question for astronomers and biologists. I do know that, whether there are or aren't extra-terrestrial creatures, philosophy offers tools for thinking about humanity's place in the universe. Just as Scipio's worries about the Roman Empire abated, our worries may abate too.

I was still troubled by my impending move away from Groningen. Once the train arrived I beeped my travel card and wheeled my luggage out onto the station concourse, standing amid the swoops of concrete facing the main streets. It was almost midnight and the scent of wet leaves hung in the air. I breathed in the night, tasting the canal under the rain, and began to walk home. The art museum loomed to my right, neon cubism run amok. Cobbles glistened. My suitcase humped over the uneven pavements. The city was old and solid, and it made me feel reassuringly small. Its rambling history yawned far before me and would stretch long after me. I was home. (pp.163-170)